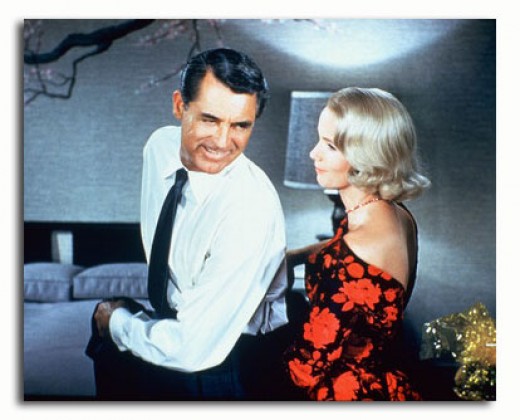

Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint

North By Northwest was filmed in 1959 but has a familiar, thematic ring unmistakably reminiscent of The 39 Steps, made twenty-four years earlier. First, North By Northwest is about buildings and architecture. By this time, Hitchcock was fascinated with them: their beamed foundations; cross-hatched construction; shining, lofty glass windows and artistic integrity. He utilizes some of the most famous buildings in New York City as well as the statuesque faces of Mount Rushmore and a phenomenal Frank Lloyd Wright house.

After buildings and trains, the movie is about advertising executive, Roger Thornhill, played by Cary Grant. He plays the archetypal ad guy: slick, the gray suit, polished, handsome, smart wry-humor, confident, plenty of cash on hand. The movie begins as did The 39 Steps, and many other Hitchcock thrillers, when our hero’s life is flowing at its usual every day pace but is suddenly interrupted by chaos. Roger Thornhill is rushing off the elevator of an imposing, downtown building delegating orders to his secretary, who must follow him out to the street taking notes. With the way these street scenes are filmed, there is the sensation of all movement taking place on conveyor belts.

Thornhill’s life is so robust and his calendar so full of client-meetings that his secretary must ride with him in a cab in order to scribble it all down as he dictates. Cary Grant hops from elevators to sidewalk curbs to the glistening marble halls of the Ambassador Hotel like a sleek gazelle and then glides into the bar for a martini with his somewhat dazzled clients. Then, by a sheer case of mistaken identity, two glorified thugs whisk Thornhill off to the sprawling, remote neighborhood of a country mansion.

The lurking captors, like pompous vultures, make homicidal threats. And just as Hanay in The 39 Steps, the innocent Thornhill has been spirited away into the underworld of espionage and murder. Thornhill’s captors, for all of their snobbish arrogance, (James Mason Plays an exceedingly articulate Phillip Vandamm), seem rather dim-witted at figuring out a way to keep their hostage subdued. They force a bottle of bourbon down his throat to render him useless; but, they underestimate Thornhill’s threshold for liquor. He is definitely smashed – lolling his head around and singing out of key, but he is an advertising guy, and ad guys can drink! Soon Thornhill manages to thwart his captors, but now, like Hanay, he must solve his own case. He enlists his mother for a while. A well-heeled, attractive, middle-aged bridge-player played by Jessie Royce Landis, (who was really too young to actually be his mother); she is the essence of sarcasm and incredulity: being an experienced woman, she does not trust her son, but she keeps him amused.

Then there is the beautiful blond on the train, just as in The 39 Steps, but this blond, played by Eva Marie Saint, appears to be much more helpful! She is mostly well equipped for some very steamy scenes, 1950’s style, in the train compartment, as well as conducting our Thornhill onto a Greyhound bus and out to the flat, Midwestern boonies, where, at a crossroads, Thornhill stands alone and waits for the famous airplane, chase-scenes. The dry, brown American landscape is nothing like the Scottish highlands: and this alone seems to render his plight more harsh. Hitchcock somehow understood the good and the bad of our country: revering 20th century progress and the great, gleaming architecture of downtown Manhattan and the gifted architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright; yet, while at the same time, pointing out the prosaic and the petty-mindedness that is stitched into the fabric of our relatively young culture.

The director was also acutely aware of the strict controls that society wants to place on us, and of the ordinary citizens who will eagerly volunteer for the cause of entrapping an innocent man, as in Thornhill’s Grand Central Station getaway, where police guards stand peering through the crowds for the killer, and a ticket taker who keeps a photograph of Thornhill near the bars of his station ready to be the one to identify him. Or when Thornhill pops up once again to meet his killers at a silent auction and the well-dressed elite turn up their noses, one woman archly calling him “an idiot”, and an auction attendant who, with pursed lips, quietly phones the police.

The film’s pace is magnified throughout by the fantastic, sonorous base and viola symphony music of Bernard Herman. The music is on the same grand scale as the architecture, including the Wright house in which high-angle, camera shots bring the suave Grant down through the stylish, textured surfaces to yet another escape.

Hitchcock had a keen sensibility for the spy and counter-spy machinations of the cold war era. He puts particular emphasis upon the role of Washington in those high-stakes international, political games. And with a clean swipe, the director suggests that the White House and “the U.S. Intelligence Agency” are covertly involved in all of this. Yet, the faces of the presidents in the Mount Rushmore Monument seem to look worried, austere as well as enthralled at what is going on after their time.