In reading Paul Theroux’s short story, Action, which appeared in

The New Yorker, (August 4th, 2014), one can’t help but draw parallels to James Joyce’s Araby from the beloved short story collection, Dubliners, (1914). Both Action and Araby comprise a boy’s coming-of-age in a working class neighborhood with very little money and a mother who has died.

Theroux’s Albert lives in Boston with his father, a shoe salesman, who uses gruff-love and over-protectiveness – a father who relies on not only his sense of smell but a keen, sixth parental sense to deftly sniff-out where his son, Albert, has been and what he has been up to.

The way my father worried about me made me think I was dangerous.

Albert’s father is overly suspicious as well as thrifty: as if he’d been through World War II and had to conserve everything including words.

“Where?,” meaning, “Where have you been?”

And, “No Eddie,” meaning Albert is prohibited from seeing the older Eddie, whom Albert’s father considers a bad influence.

The story takes place during a time when doughnuts cost a dime, yet, Albert’s father is hard pressed to dole out a little spending money for his son, just as the boy in Joyce’s Araby, does not receive a shilling for the bazaar from his uncle until it is almost too late to go.

In Araby, both parents are apparently dead, so that the boy lives with his aunt and uncle, and possibly for this reason, Joyce’s Dublin boy has more freedom than Albert has. The boy is allowed to go to the bazaar and take the train to Araby by himself late at night – not as an errand but, conceivably, to have fun.

Theroux’s Albert rides the Boston train specifically to run errands for his father, but these chores across the city into its shadowy corners become a catalyst for discovering himself and learning more about his father. For Albert has learned that both he and his father have two sides.

Albert encounters a number of nefarious characters along the way and starts to feel as if he’s been running or “escaping” the whole way. When he finally reaches the warehouse of his father’s vendor, the man behind the counter is unfriendly,

He didn’t greet me or even comment.

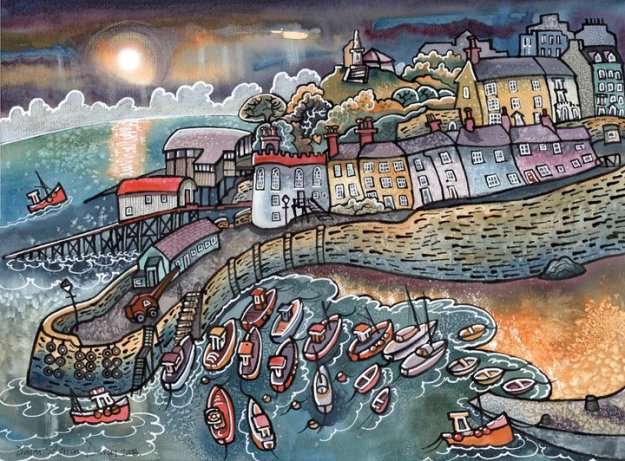

There is an intense feeling of alienation. In the process of blindly and innocently exploring the city, Albert has embarked upon a personal odyssey leading to some profound revelation. As well in Araby, the boy rides the train to Araby amidst a palpable sense of isolation as he sits alone, oppressed by the crunch of the city. Then, once inside the bazaar, he also encounters an unfriendly and “not encouraging” welcome. The milieu of the bazaar has become dark and hushed, its tables mostly bare, its broad catacombs empty yet open to the night sky, and this is where Joyce leads up to his epiphany.

I recognized a silence like that which pervades a church after a service. I walked into the center of the bazaar timidly.

Both boys linger at shops to look at or buy something and they both receive similar versions of indifference and contempt from the people there. Both say “No” when asked whether they want to buy anything from a selection of what now seems to be only meaningless objects. Still, amidst the harshness and shame, love or compassion seem to come exclusively from a parental figure or a neighborhood girl.

In Araby, and all of the Dubliners tales, Joyce is exquisite in a way that is rarely found in today’s literature. Yet, Theroux describes the provocative smells and anxt of the city more poetically as he treks deeper into the streets:

Now it was a summer afternoon of hot sidewalks and sharp smells and strangers, the air of the city thick with humidity under a heavy gray sky. It all stank pleasantly of wickedness, and if I’d known anything I would have recognized it as sensual.

This harkens to Araby and Joyce’s ash-pits of the back lanes that are “odorous” and damp and “filled with odours.” Joyce’s lyricism, alliteration and repetition have made every line of the Dubliners stories poetry, as with his alliteration in, “silent streets, dark, dripping gardens, and feeble lanterns,” and the sublime image of his love, the neighbor girl across the way: “The white curve of her neck,” is repeated twice in the tale and held in his mind as a holy image…

I was alone at the railings. She held one of the spikes, bowing her head towards me. The light from the lamp opposite our door caught the white curve of her neck, lit up her hair that rested there and, falling, lit up the hand upon the railing.

Joyce infuses the boy’s infatuation for the girl with poetic, holy enchantment. Just thinking of her image under the light and brooding over the events that will lead up to seeing her again throw the boy into an existential crisis. He wanders through the house and murmurs “O love! O love!” in a kind of prayer.

The syllables of the word Araby were called to me through the silence in which my soul luxuriated and cast an Eastern enchantment over me.

The boy’s passion is so thoroughly described – the way it interferes with his usual life, which seemed now “child’s play,” that it is hard to believe he is only a boy. He mourns, “my eyes were often full of tears,” and, “Her name was like a summons to all my foolish blood.” Indeed, he bares a chalice for his love, “safely through a throng of foes,” as he shops at the outdoor markets with his aunt.

Whereas Joyce’s boy in Araby is filled with passion for the neighborhood girl, Theroux’s Albert seems not to have reached such levels of fervor. Upon meeting Paige, Albert admits to being, “out of my depth.” He stands in Paige’s doorway, but she can’t see his face, as he is backlit by the sun – a sort of reversal to Joyce’s light from the lamppost illuminating Mangan’s sister.

Paige is described with admiration and the kind of sensuality that doesn’t quite know where it is leading. Her face is framed by wisps of hair as she works at an ironing board, and there is a lingering reminder of Mangan’s sister in Araby by the way Paige “bowed her head and went on ironing.”

With many parallels in the two stories: not least of which is in their settings, as in Action depicting “houses that all look alike along the hill,” reflecting the houses in Araby which “gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces,” Albert is actually more lonely than the boy in Araby. Albert has a rather dismal, secluded life living under the strictures of his father, while Joyce’s boy in Araby is not isolated until he falls in love. Before this he is part of a tribe of the neighborhood children. However, both reach a crisis point in which a crucial truth comes to light. Joyce seems to have invented it: the literary epiphany, where there is an unexpected, and often simple, sudden insight or revelation that ends the tale.

“Action” is included in Paul Theroux’s book of short stories, “Mr. Bones”

James Joyce’s “Dubliners” includes “Araby,” one of only three of the tales told in the first-person.