The classic children’s book, Wind in the Willows, was published in 1908 and originally began as an antipodal exchange of short stories. The author, Kenneth Grahame, was a banker by trade who worked in the city during the week and would write letters home to his young son, affectionately called, “Mouse”. These letters were actually continuing stories about animal characters who lived by the river Thames and had adventures on the river and in the English countryside, presumably in such places as Wiltshire and The Berkshire Downs, as well as in the forest.

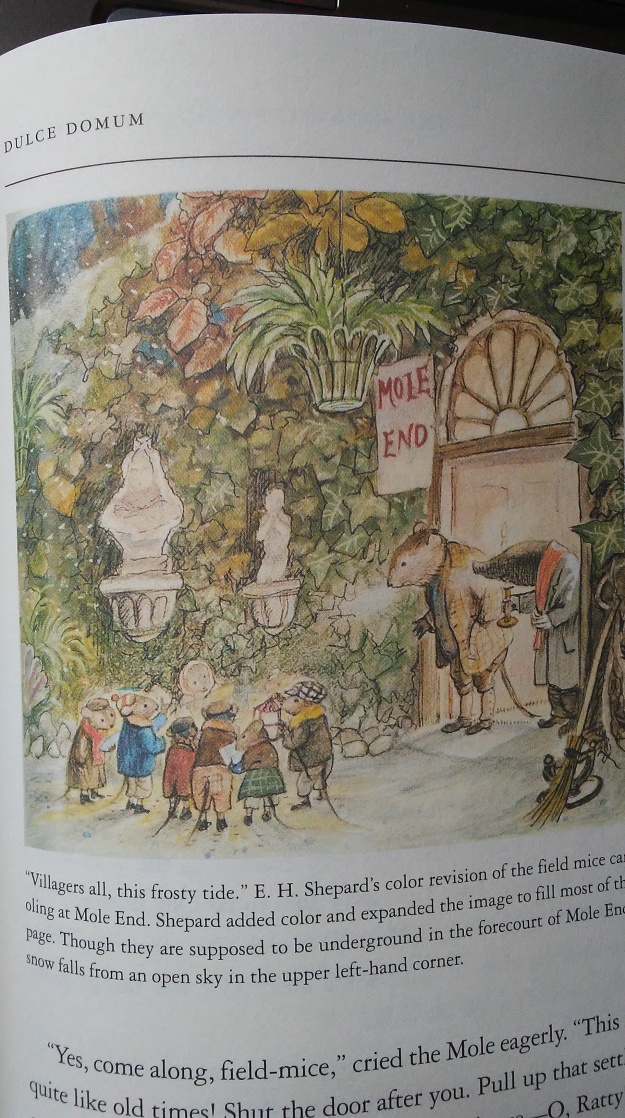

Grahame describes generously, often poetically, the details in nature from a personified animal’s point of view, their adventures on the wide uplands and streams, along the river’s tributaries, bubbling brooks, runnels and little culverts. The animals, especially the Water Rat, have great escapades and picnics throughout these ebullient pools and backwaters. They go deep into the forest, too, and visit caves and underground tunnels that have been made into grand or quaint abodes, as with the Badger’s catacomb mansion underground and the Mole’s simple hideaway that he nevertheless calls home.

Ratty, the Water Rat, the wise, good-humored, avuncular animal in the story might be considered the main character, and yet, little Mole, who is naïve, impetuous, curious and childish, holds the center-stage, (that is at least when Mr. Toad is not hogging the limelight with his wild exploits). Mole starts out essentially blind to the world outdoors. Indeed, it seems as if Mole is born as the story of his adventure begins. As if in an underground liminal zone, he has been living for years doing nothing but scratching around for provisions and whitewashing his lair in the spring. His eyes are suddenly opened; he hears the birds singing for the first time, and when he reaches the river, he stops spell-bound… Mole has never seen the river before. Here, Grahame describes with Wordsworthian celebration, the spring that Mole wakes up to:

Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lovely little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing….

He sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him a babbling procession of the best stories in the world. Sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

When Ratty and Mole meet, they become fast-friends whose friendship grows and develops as that of a blossoming, childhood friendship. Yet these characters are not so much like children as they are like people that children can relate to and learn from. Certainly, the story is a classic that can absolutely be enjoyed by both adults and children. Ratty and Mole perform great adventures on the river, including a very funny scene in which Mole impatiently tries to take the oars from Ratty. They have picnics and meet many other animals who live by the river. There is an intricate system of social order and yet a warm comradeship among the various animals. Most of them are rather sophisticated, especially Ratty’s closest chums; they speak in an elevated English, and wear stylish outfits. Ratty, however, is more wise than most, and often circumspect or patient when the other animals are not as poetic or naturally insightful: as if the Water Rat were worldly-wise, though he lives only by the river in the English countryside. Still, each animal has the gift of natural instincts, much like that of humans, but the natural, more super-instincts, that inter-communication of animals – of sensing when they are close to home or when some danger is afoot. Indeed, Grahame humanizes the animals with great charm:

“Who is it this time, disturbing people on such a night? Speak up!”

“Oh, Badger,” cried the rat, “let us in, please. It’s me, Rat, and my friend Mole, and we’ve lost our way in the snow.”

“What, Ratty, my dear little man!” exclaimed the Badger, in quite a different voice. “Come along in, both of you, at once. Why, you must be perished. Well I never! Lost in the snow! And in the Wild Wood, too, and at this time of night! But come in with you.”

In and among this milieu of sodality and amidst these various expeditions with a handful of close friends, Ratty and Mole maintain the closest bond. Theirs has become a cultivated friendship. They have had their little adventures, their strolls far-afield, for example, where they mingle with humans in society: paying a porter at the train station, lodging a complaint to the police… where, in the evening, they see people sitting by the fireside through their living-room windows along a cobbled sidewalk in the village. Ratty and Mole’s relationship has endured the perils of lovable, capricious, reckless Mr. Toad. Mole is going through some changes. He is growing as an individual and as a mole.

As for Toad, he learns a few of life’s lessons, for sure, despite his insanely impulsive craving for cars and boats, or anything with a motor. Toad experiences the revelation of hope even at his lowest point, in jail, when the goaler’s daughter brings in a hot, fragrant meal. The aroma fills up his cell, and suddenly his old aspirations and dreams return and he sees a solution to his problems – scolding himself for becoming so morose, thus, hope springs eternal, might be Toad’s credo, even in the face of his shortcomings. He has a long conversation with the gaoler’s daughter, which is a more intimate example among Grahame’s portrayals of an encounter between an animal and a human. Still, Toad is possessed by a perpetual wild hair combined with his compulsive lying. Promising the train driver, for instance, he’ll wash the driver’s shirts in exchange for a ride home, knowing full well he won’t send them back, yet passionately believing he will wash the man’s shirts and send them on, once he returns to Toad Hall.

Whether or not Toad changes and matures for good: this is only implied at by the restraint he shows in front of his friends by not indulging in self-centered speech-making and hogging the limelight at the Toad Hall party. But we the audience perceive how capricious Toad can be. He’s tricky and holds his cards close to his chest. Therefore, only the author really knows if Mr. Toad has actually changed.

Ratty has remained throughout: wise, clever, sociable, yet circumspect, good-humored and adventuresome; perhaps Ratty has become more so, in every quality. The other characters are not as delved into; they are who they are. However, Mole has changed as a central character. He has transformed from a naive, myopic little animal living in a narrow hovel underground into a more knowledgeable; indeed, wise; well-traveled (albeit of the English countryside, villages and forests); more experienced and sociable mole who has learned true comradeship and has in fact performed brave, heroic and kind deeds since he left his lair and unwittingly enrolled in the apprenticeship of the Water Rat. Even Badger gives his nod of approval by calling Mole, “clever Mole” and “good Mole,” tributes that Toad jealously covets from anyone, but especially from practical, austere, fatherly Badger.

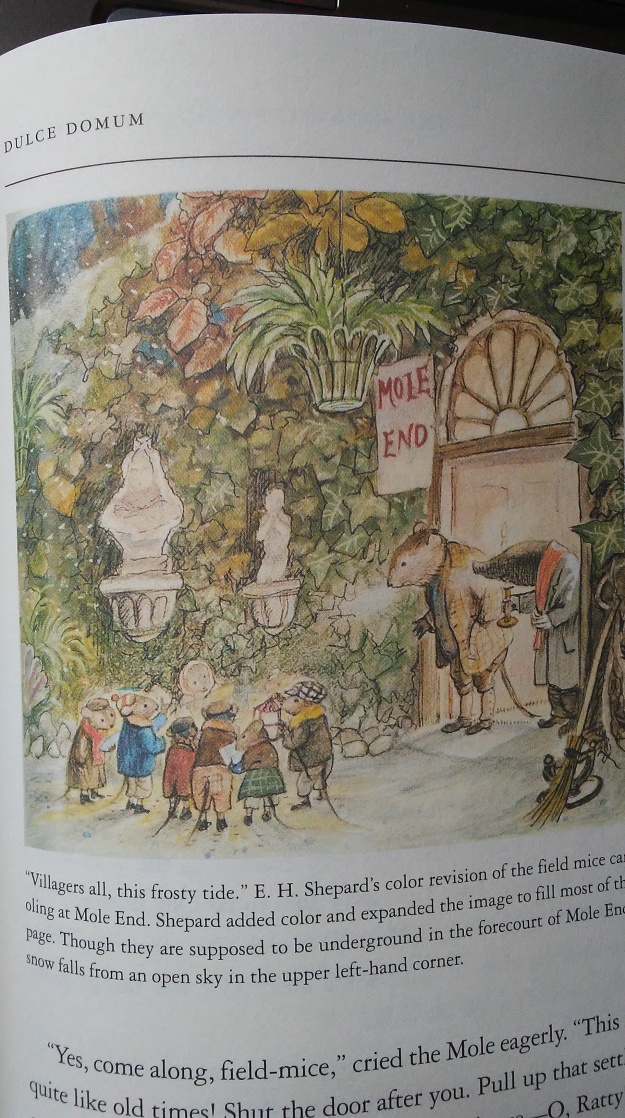

When choosing your copy of Wind in the Willows, any book will do as long as it contains all twelve chapters. I found one large, hardbound version with the most beautiful illustrations that I’ve ever seen for this book, however, it was missing chapters. Oddly, the chapters that were left out happened to be some of the most magical, mythical and mysterious chapters of the entire story, such as: Piper at the Break of Dawn, Wayfarers All and the unedited The Return of Ulysses. To have these chapters is to enjoy the full enchantment of Grahame’s genius.