Out of his collections of short stories, The Rich Boy (1926) is one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s best pieces. Today the tale might be called a short novella; it has also been deemed a psychological study of the advantaged. It is the story of a young man born into wealth and how he responds to love, relationships and issues of money and status within his upper-class, Fifth Avenue inner-circle.

Fitzgerald begins by depicting rich people almost as if they are a separate race – “they are different,” the narrator explains:

“They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are… Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are.”

Fitzgerald made the art of characterization seem easy. He molds his characters quickly as if with a painter’s brush, so that I feel I know them perfectly. Their gestures, body-language and thought-processes flow smoothly from the palette, yet his people are not boring stereotypes. Indeed, Fitzgerald himself had this to say about characterization:

“Begin with an individual, and before you know it you find that you have created a type; begin with a type, and you find that you have created – nothing. That is because we are all queer fish, queerer behind our faces and voices than we want anyone to know or than we know ourselves.

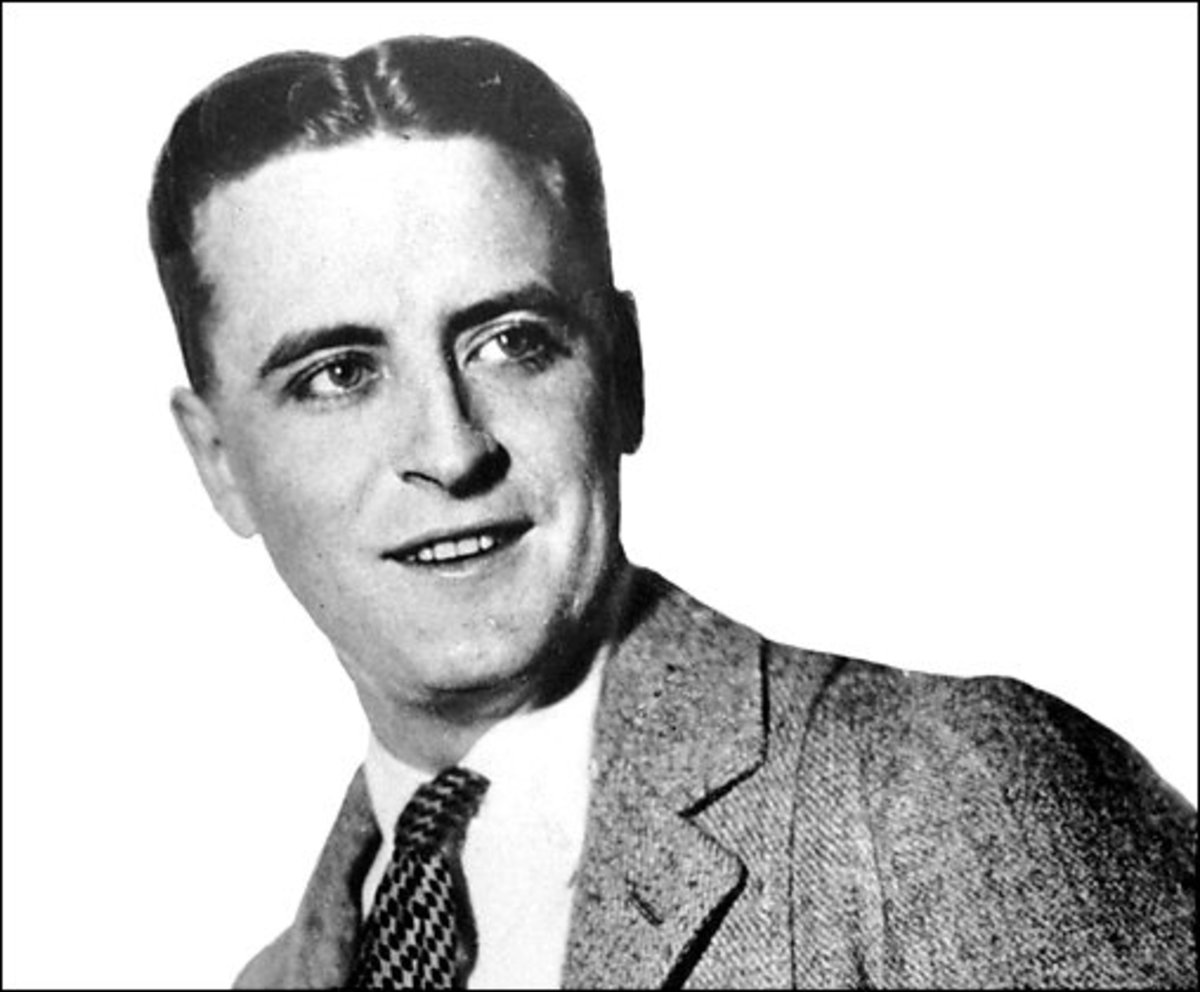

Fitzgerald was among the writers and artists of the “Jazz Age,” a term he invented himself.

Fitzgerald was devoted to Zelda, though they had a distressing relationship.

The main character in The Rich Boy, Anson Hunter, grows up having an English governess so that he and his siblings learn a certain way of speaking that resembles an English accent and is preeminent to middle and even upper-class American children. Thus, the people around him know he is superior – they know he is rich by just looking at him.

The tension of the story begins right away – with his fitful love for Paula, and an iffy engagement, tinged with the kind of alcoholism that deviously thwarts everything in sight. Anson is a man who lives in separate worlds during the glittering, glamorous, roaring 20’s, when everything seems impossibly affordable – big houses, flashy cars, Ritzy nights on the town. Yet, his stories take a turn, just as the Stock Market did at the dawn of the 1930s. Fitzgerald’s settings are bewitching. Today some of the vernacular might sound old fashioned, yet, the efficient punch of its delivery stands as a first-rate testament to the writer’s craft!

Everything about Anson creates tension. Even his wealth and his absolute capability cause apprehension. Then there is the awful hold that alcohol has on him and the maddening indecision it creates between Anson and a real commitment to Paula – or any woman. Finally, the way Anson goes about counseling all of the couples in his “circle” yet cannot maintain a lasting relationship of his own. This compulsive-will to verify himself as a moral, respectable, mature man of New York society by patching up difficulties in other marriages proves to be an irreparable flaw in Anson’s character. The conflict builds up to a sad denouement when Anson begins dutifully setting about putting an end to the illicit affair of his uncle’s wife, Edna. And when his machinations turn out badly, Anson takes no responsibility for the tragedy.

Ernest Hemingway wrote about his friendship with “Scott” in, A Moveable Feast, set in Paris.

I want to like Anson even as I realize that underneath all of his glamour and devotion to high society and tradition of family posterity, he is really suffering inside with alcoholism. This handicap, or tragic flaw, gains my sympathy. However, Anson’s ultimate indecision in regards to commitment and real love, his hyper-vigilant need to interfere in the affairs of others, begins to strike me as infuriating – and of course, this very lapse in character adds to the tension of the story.

Fitzgerald’s propensity for describing a bar-scene at the Yale Club or the Plaza Hotel became thematic to his tales and, upon further reading, takes on a recurring vignette from one tale to the next. Yet, I find myself lapping up these settings that involve stylish bars and hotels, because they are so well articulated, from the clever dialogue at the bar with a bartender or drinking-companion, to the colorful yet moody renderings, to the inevitable infatuation with glamorous women and the way these motifs affect Fitzgerald’s heroes.

I think of Hemingway’s, A Moveable Feast, throughout Fitzgerald’s short story; because, in Hemingway’s novel he describes Fitzgerald’s terrible weakness for alcohol. I also think of, The Razor’s Edge, by Somerset Maugham, perhaps because of its detached yet familial narrative style.

Fitzgerald, in a style all his own, offers shocks of unexpected sensitivity and wisdom, which seem somehow surprising. I almost worship the writer’s vocabulary and his way of forming a phrase, such as – “rapt holy intensity” when describing the lovers. Or Anson and Paula’s “emasculated humor:” I found this such an apt way of describing the initial repartee that occurs between two people who are falling in love inside their own profound, yet rather childish, bubble.

“Nevertheless, they fell in love – and on her terms. He no longer joined the twilight gathering at the De Soto bar, and whenever they were seen together they were engaged in a long, serious dialogue, which must have gone on several weeks. Long afterward he told me that it was not about anything in particular but was composed on both sides of immature and even meaningless statements…”

Fitzgerald was contracted to write screenplays for Hollywood at two separate stages of his career, though he contemptuously viewed it as “whoring.” The author inserts himself briefly, however lightly-concealed, into Anson’s life:

“…one (friend) was in Hollywood writing continuities for pictures that Anson went faithfully to see.”

Thus the interweaving of fiction and autobiography! The glamour and infamous history of the writer himself affects the impact of his tales; yet, whether a reader knows about the writer’s life or not, Fitzgerald’s works are treasures!